AgroBIG is a joint initiative between the Ethiopian and Finnish governments launched a decade ago aimed at promoting agribusiness development. The programme’s first phase focused on organisational development and partnership building in the Amhara region, supporting capacity building and providing access to finance for value chain actors in the selected value chains such as rice, onion and maise. Ending in December this year, the second phase, with a budget of €10.3 million, sustains the achievements of Phase I and strengthens agribusiness in the Tana sub-basin. It has an expanded target area and supports a total of eight agricultural production administrative woredas, and additional value chains such as tomato, dairy milk, goat and sheep fattening, and egg and poultry meat production. AgroBIG emphasises value addition, job creation, and market linkages, while promoting the inclusion of women, youth and persons with disabilities (PwD). The value chain approach addresses bottlenecks and supports various actors in adding value to their produce, improving competitiveness and profitability.

AgroBIG's monitoring approach and activities has focussed on different stages of the agricultural value chains, from production and processing to marketing and distribution. It involved monitoring key indicators and variables related to agricultural practices, input availability, productivity, quality standards, market dynamics, and income generation, among others. The programme has employed a diverse range of participatory techniques, including external evaluations and studies by short-term consultants, regular reviews conducted with technical and steering committees, as well as annual surveys on selected indicators. These practices served to inform project stakeholders about both the achievements made and the persistent issues that require attention

In retrospect, Mezgebu believes there are many ways in which AgroBIG could have benefitted from futures-thinking.

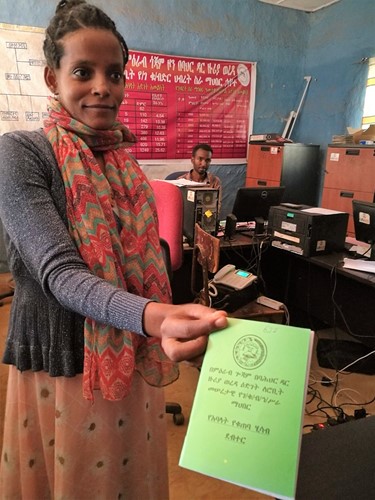

An AgroBIG beneficiary of women's cooperative, Amhara, Ethiopia. Photo: Petra Mikkolainen, 2019

An AgroBIG beneficiary of women's cooperative, Amhara, Ethiopia. Photo: Petra Mikkolainen, 2019