Insight

We think we have the right answers, but we are often asking the wrong questions

A user-centered design process is where communications are tested by those they are intended to reach.

Insight

A user-centered design process is where communications are tested by those they are intended to reach.

Although, I have been practicing and teaching design and communication all of my professional life, I had, until I started to work in a GIZ development project in India, very little understanding of the theories and strategies that influence design, communication and behaviour.

When, one day, I was asked to design ‘only a poster’ to inform and educate workers about Social Security for Unorganised Workers in Karnataka, India, I knew that something was really wrong with the job. I learned that 94% of the entire Indian workforce were so-called unorganised workers (UOW) and that, due to this GIZ pilot project, 20 million UOW were expected to join the social security scheme.

Could I design a poster that tackles such a complex topic? What did I know about the workers and how they communicate and perceive images? Why would they sign up for a social security programme after seeing a poster?

I felt the need to find out more. Thus, a small team consisting of a film maker, translator, a social worker and myself, set out for a remote village to interview potential beneficiaries. We took with us the expensively printed GIZ brochures, designed by an agency to inform the target group, which we showed to the UOW in the village, asking the simple question: “What do you see?”

The first image was a cycle rickshaw, the second an icon of a wheelchair, and the third a photo of men, meant to represent UOW.

But the interviewees could not make out what the representations showed. They had never seen a cycle rickshaw as it only exists in North Indian villages. Likewise, the image of the wheelchair as, in a South Indian village, nobody possesses a wheelchair or has ever seen one. The icon, commonly used in international airports, was unintelligible for the villagers and definitely did not represent ‘differently abled’, as intended. Finally, a female participant pointed at the photos of the UOW and said: ”The men in the photos look drunk and frighten me”.

The visual explanation of social security insurance was tested among unorganised workers, asking them: "What do you see?"

In a nutshell, that’s how I learned about the importance of visual semiotics in a cultural context.

The visual language globally used to communicate on the internet and other media does not relate to the semiotics of workers in a South Indian village. The interpretation of images, symbols and graphic language depends greatly on cultural language. There is very little uniformity between different cultures.

Towards the end of our interviews, we handed out the brochures to the female workers in the village and asked them to read the text. Some were looking at the printed text with a blank expression on their face. That’s when we realised many of them were illiterate and ashamed to admit it.

To make matters worse, the words SOCIAL + SECURITY + INSURANCE carried no meaning for the villagers. As daily wage labourers, they lived without a bank account, pension scheme, health insurance or any other security. Insurance was a foreign concept. So why would they be interested in it?

Internet research led me to UNICEF’s Strategic Communication for Behaviour and Social Change in South Asia where I found the following guiding sentence:

"Strategic communication is an evidence-based, results-oriented process, undertaken in consultation with the participant group(s). It is intrinsically linked to other programme elements, cognisant of the local context and favouring a multiplicity of communication approaches to stimulate positive and measurable behaviour and social change."

Here it was: To change behaviour - so that participants engage with a programme - a lot more is needed than brochures and a poster. Additionally, I turned to UNICEF’s Human-Centred Design, a guide on how to identify and design solutions that directly involve the users they aim to serve.

We went back to the drawing board to understand the visual and cultural perceptions of the programme participants and the barriers to behavioural change that come in many forms such as emotional, societal, structural, educational, and familial.

The next step in developing a communication campaign with UOW was to convince the decision makers - GIZ and the Indian Ministry of Labour - that we needed a strategy to engage potential programme beneficiaries. This strategy should be culturally appropriate and communicate with illiterate participants. It could only be developed successfully if the beneficiaries played an active, participatory role in its design and implementation.

With UNICEF’s strategies in hand, I started on a learning expedition about communication and design in development, which changed my thinking and my practice. We set up a research process and used the user-centered design process. We tested our designs with the participants asking what do you see? We had to redesign our visuals multiple times as what we thought would work did not communicate well with the participants. Developing, testing and redesigning the graphic-design was of utmost importance, since the majority of the mostly illiterate participants were very specific about the visuals.

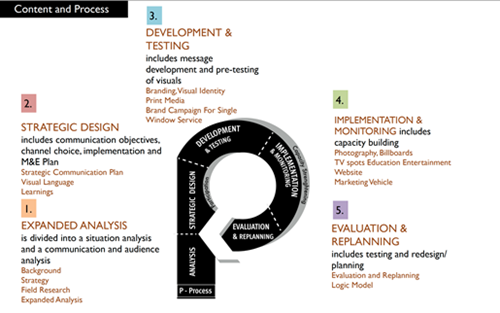

The P-Process was adapted for the GIZ programme. The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs (CCP) and its partners in the USAID-supported Population Communication Services project developed the P-Process in 1982 as a tool for planning strategic, evidence-based communication programmes.

After many attempts, we finally succeeded and implemented a communication strategy that led to a measurable success of knowledge about social security among UOW. In a survey conducted in 100 villages where the communication programme had been rolled out and 50 where it had not, awareness and utilisation of social security schemes were 13% and 15% higher, respectively, in those with the programme compared to those without.

Today, I am convinced that development is a communicative process. There is no development without communication, as Erskine Childers, the Communications for Development (C4D) pioneer stated in 1968. “If you want development to be rooted in the human beings who have to become the agent of it as well as the beneficiaries, who will alone decide on the kind of development they can sustain after the foreign aid has gone away, then you have got to communicate with them. You have got to enable them to communicate with each other and back to the planners in the capital city. You have got to communicate the techniques that they need in order that they will decide on their own development. If you do not do that, you will continue to have weak or failing development programmes. It's as simple as that. No innovation, however brilliantly designed and set down in a project plan of operations, becomes development until it has been communicated.”

Part of the research was to find out which communication devices our participants used: 79% owned an average of two cellphones with basic technology per family. Of these, only 15% used it to send/receive SMS; 19% used phones to listen to radio stations. None of the participants had access to internet.

Many of you might be in the situation I experienced. You might be wondering how, rather than targeting people, you can involve them in your communications work so they start steering their own course of change. What could that strategy look like? How will you design and implement it?

I have put together some C4D resources to help get you started. It is by no means a complete collection, rather just a snapshot. There is a lot more out there. I welcome your feedback and, if you wish to add to the content, feel free to send me an email. This is a living document and will be regularly updated.

Watch this short video of the user-design testing process in the GIZ project. You can also check out this online publication about the design process.

Sabina von Kessel

Sabina von Kessel is the communications and design expert for Skills Initiative for Africa (SIFA), Funding Facility (more info here). Originally from Germany, she lived for more than a decade in India before moving to South Africa. Sabina has over 30 years of experience in the design of communication strategies and products and teaching visual communication. Her interest lies in a human-centered approach to design, applying theories and strategies of Social and Behaviour Change Communication.

sabina.vonkessel@skillsinitiative-for-africa.com

Tel: +27 (79) 387 66 70

Contact