Insight

Turning down the heat: how breweries are rethinking energy use

Insight

Not every process suits a heat pump, but for the right applications, the savings can be substantial. If there’s one thing every brewer knows, it’s that you can’t make good beer without heat. It’s everywhere in the process, mashing, pasteurising, cleaning, kegging. But as the industry gets more serious about cutting carbon, the way we generate and use that heat is coming under closer scrutiny.

Heat pumps are not a new technology, but they’ve come a long way and are now offering some very practical opportunities for breweries looking to decarbonise.

“I’ve had a lot of conversations with brewers who are keen to implement heat pumps, but aren’t sure exactly where to begin. Heat pumps have huge potential to decarbonise in a cost effective way, but they need to be matched to the right processes,” says Mike Bannerman, Sustainability Consultant at NIRAS.

And it’s not just brewers asking these questions. Across the food and drink sector, many producers, from dairies to bakeries, are facing similar challenges. Processes that rely on steady, lower-grade heat are common across the board, and that’s where heat pumps can really deliver.

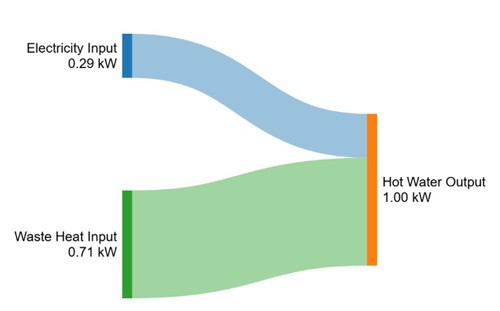

At their most basic, heat pumps do something quite simple: they capture waste heat and “upgrade” it to a higher temperature so it can be reused elsewhere in the system. That means less reliance on gas boilers, and fewer emissions from your heating processes overall.

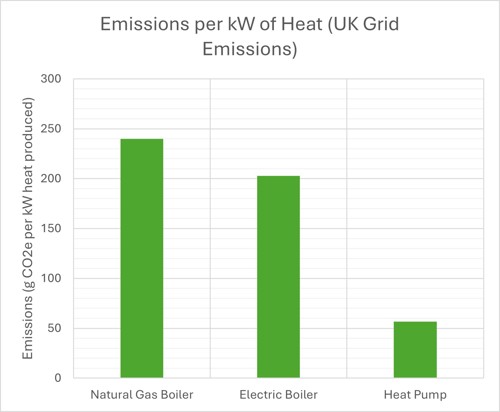

Heat pumps typically produce around three units of heat for every one unit of electricity used—far more efficient than a gas boiler, which usually needs 1.25 kW of gas to deliver just 1 kW of heat, or an electric boiler, which is strictly one-to-one. And because grid electricity in the UK is rapidly decarbonising, that efficiency translates into a significant carbon saving too.

In fact, the Food and Drink Federation has estimated that the food and drink sector could cut its emissions from heat by as much as 64% by 2050 using technologies like this. That’s a big number—but not an unrealistic one, provided we apply the tech where it fits best.

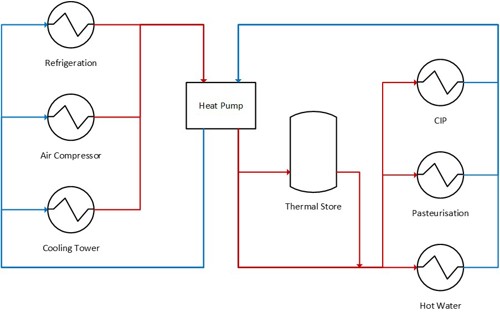

Most brewers don’t think of fermentation as a source of energy, but it gives off a fair bit of waste heat. While it’s not perfectly consistent, it’s surprisingly steady—and that makes it a good candidate for feeding into a heat pump.

“Fermentation is actually a great source of low-grade heat,” Mike explains. “It’s not high temperature, but it’s stable, and usually linked to a chiller plant. If you can utilise the waste heat from the chillers, you’ve got a ready-made input.

From there, one of the strongest use cases is in the packaging hall. Tunnel pasteurisation for example tends to operate at 60-70 degC with generally steady, continuous heat demand—pretty much ideal conditions for a heat pump. Keg washing is another good match—again, you’re dealing with hot water rather than steam, and a predictable load once things are up and running.

“Packaging areas are ideal. The lower temperatures mean there is limited demand for steam, you’ve got consistency, and you’ve got demand. It just lines up nicely,” says Mike.

That same logic applies across many food processing sites, too. If you’re running a bottling or canning line, operating thermal processing, or pasteurising product, chances are you’ve got heat demands that fall well within a heat pump’s comfort zone.

On the flip side, the brewhouse is trickier. The loads are higher, more intermittent, and often scattered across different users. Steam is still preferred for these processes, and heat pumps just aren’t quite there yet for those kinds of high, fast demands.

“That doesn’t mean there’s no role in the brewhouse,” Mike adds. “There’s definitely potential for things like preheating water, which can take pressure off your boilers. But a fully centralised heat pump system? That’s a harder sell.”

We recently worked on a design project for a large UK brewery looking into exactly this. The site was considering a specific sized heat pump system to help decarbonise its operations. We looked at everything—from energy balances and electrical capacity to infrastructure layout and cost modelling.

The projected outcomes included a 40% decrease in Scope 1 emissions and a 33% improvement in heating-related cost efficiency.

“The numbers speak for themselves,” Mike says. “It’s not just an environmental win, it’s operational savings, too. And that’s what gets people really interested.”

And this isn’t just something for the big players. A 2.5 MW system, for instance, could save around £280,000 a year and reduce CO₂ emissions by 2,600 tonnes annually. That’s the equivalent of taking more than 450 cars off the road, or sending them all the way around the world and back again.

Food and drink manufacturers of all sizes can tap into these kinds of efficiencies, especially in areas with stable, repeatable heat demands.

Of course, installing a heat pump system isn’t done instantly. You need to consider how heat and cooling demands line up, whether your electrical infrastructure can handle the load, and how best to distribute the recovered heat. It takes some upfront planning, especially if you’re looking at larger systems that might require a grid upgrade.

“One of the biggest concerns is often around electrical capacity, especially for larger systems,” says Mike. “But it’s worth remembering that heat pumps typically deliver around three units of heat for every one unit of electricity. Compare that to electric boilers, which are one-to-one, and suddenly the demand doesn’t look so steep. Yes, you’ll need to plan carefully, but in many cases, heat pumps actually put less strain on the system than the alternatives.”

That’s why a phased approach tends to work best. Start with the low-hanging fruit—packaging, kegging, pasteurisation. Learn what works, then build out from there.

Are heat pumps the answer to every sustainability challenge in brewing? No, of course not. But they’re one of the more accessible, lower-risk ways to start moving the dial. They don’t require a fundamental change in how you brew, they don’t compromise quality, and they can often work alongside your existing systems.

“It’s not about chasing perfection,” Mike says. “It’s about progress. And heat pumps are one of the most readily available, pragmatic ways to start.”

The key is understanding where they make sense, and acting on that insight. Because as energy prices rise and regulations tighten, the producers who’ve taken the time to get ahead of the curve will be in a far stronger position than those playing catch-up.

Sustainability doesn’t have to mean reinventing your entire operation. It means making considered improvements based on where you are now. Heat pumps might not be the flashiest bit of kit, but they’re a smart place to begin.

Michael Bannerman

Sustainability Consultant

Burton upon Trent, United Kingdom

Adrian Nicholls

Utilities and Process Engineering Manager

Burton upon Trent, United Kingdom